Slediquette

November 2015

Oh sure, she prepared us for our adventure. She layered us in sweaters and coats and pants until we couldn’t bend, and she fixed mittens over our finger gloves because she hated to hear us cry when she had to run cold tap water over crab-slow fingers, almost frostbitten from overtime on snowy Forest Hill.

She knew we were going sledding.

After all, she and dad bought the sleds we picked out. Fearless Flyers or something like that. And she bit her lip because she knew the risks. Dad always reminded her about the time he flew down Strawberry Hill in Hannibal, guiding his sled between the front and rear wheels of a moving trolley car.

She knew all about Strawberry Hill because she grew up two blocks from there. As a child, she sledded that same hill, fearless and invincible. But that was before she became a mom.

As a mom she did all she could to make us safe.

“Watch for cars. No pile ups. Stay away from trees and curbs and culverts.” Of course, she also supplied the paraffin to wax our runners. “This’ll help you go faster,” mom promised.

She never made us wear helmets. But she would’ve fitted us in body armor if she had known what we did.

A half mile from our house, on an Ozark hill at the edge of Rolla, somebody had positioned an old Plymouth car hood as a makeshift ski jump for sledders. Word traveled fast about the sled jump, and we went straight there. It took all afternoon to work up our nerve to jump that car hood. Meantime, we raced and formed sled trains and double deckers and triple deckers. We went down the hill backwards.

About the time our fingers started tingling, a kind of brain freeze numbed our fear, and we took off down the hill to rock the Plymouth hood.

During any sledding event, it was a safe bet there would be casualties. Mainly, inanimate objects got damaged. Plastic sleds and saucers were the first to break. And the car hood, even packed with snow, lost its graceful shape. Every once in a while, we’d bend a steel runner or split a centerboard, which destroyed Fearless Flyer’s guidance system. Despite our daring jumps, rarely did we suffer anything more than a bloody nose or a loose tooth.

Always in the backs of our minds we heard the warnings from mom.

“You can get hurt if you’re not careful.” Then she’d tell the story about the kid who broke his neck, or lost a tooth or an eye. We would shudder and promise her we’d be careful. Then we’d head to the most dangerous slope and let ‘er rip over the car hood or some other makeshift jump. We were young and invincible, and we were going to live forever.

If you’re reading this passage to your toddlers, tell them not to try this. But please understand that your children, as they grow and experiment with life, will do stupid stuff like this, and they’ll never tell you. That’s just the nature of things.

We always stayed too long, even when the snow was slushy and the sledding was slow.

“Just one more ride,” we would agree, spending our last energy pulling our sleds up the hill, slipping and sliding to the start.

Then we’d go home for the warmup, and the cold water torture on near-frostbitten fingertips.

Nowadays snowboarders laugh at our 1950s makeshift sled runs. That’s okay. We used what we had. We did what we knew.

This winter when conditions are right, after a fresh snowfall, sledders and snowboarders will hit the slopes. Wherever it’s still permissible, they’ll find a perfect hill. And when they’re not texting or tweeting or taking selfies, they’ll plunge downhill to test the limits of their bravery and gymnastic skills.

But don’t tell mom.

Read more of the author’s stories at JohnDrakeRobinson.com. For more stories about growing up in rural Missouri, check out the trilogy by Bollinger County native author Stan Crader: The Bridge, Paperboy and The Longest Year.

A View From Under The Bridge

August 2015

This view might be the most fun.

Afternoon thunder roared in the distance as we unloaded three kayaks and prepared to launch into Roubidoux Creek. I paused to look up, not so much at the storm clouds, which would offer only a glancing blow, but at the giant piers that supported twin bridges over this creek.

The bridges carry traffic along I-44, and they’re the great-granddaughters of the Route 66 bridge we’d float beneath downstream.

On this day, the navigable part of Roubidoux Creek begins here, beneath the Mother Road amid the pillars and concrete sprayed with graffiti and littered with trash. We spent a few minutes deciphering the prose...and picking up some of that trash.

Then we hit the water.

As we launched our kayaks, over our heads we heard a hundred cars pass, their passengers unaware that we were about to float Missouri’s second-most overlooked stream.

For almost a mile the water twists and braids past brush piles and gravel bars and blue herons thick as mosquitoes around their rookeries. We flowed into the heart of Waynesville. Yet we never really saw the town. Not from the creek. Buildings and buzz and hubbub rose around us on both sides of this waterway. But from the water, our view was pastoral.

Roubidoux Spring gushed at us from the right, roiling from beneath a giant concrete wall where a dozen young brave souls jumped into the cold waters. The spring doubled the volume of Roubidoux Creek and lowered the water temperature 20 degrees.

We approved.

A kayak floating Roubidoux Creek is like a blood cell coursing through an artery. A lot of activity happens outside this conduit, but you don’t see it. And it doesn’t see you.

We paddled past dozens of locals along the stream bank. Kids swimming. Adults relaxing on their lunch break. Off-duty soldiers from nearby Ft. Leonard Wood were fishing...right here in this hidden waterway through the middle of town.

And then I looked downstream.

In the distance the old Route 66 bridge arched high over our path, as it has for eight decades, looking like an old Roman aqueduct with the original mother road coursing over the old span’s back through the heart of Waynesville. But drivers only catch a fleeting glimpse of us, if they see us at all. I waved at them anyway.

On our right were ball fields and soccer fields and fitness trails. Or so I was told. All we saw was green vegetation and clear spring water. We passed a giant pipe pouring thousands of gallons of purified water into the stream. That water used to be sewage. But treated, it’s drinkable, I’m told.

It looked clear, smelled good.

We paddled downstream as another thunderstorm shook its fist, blared at us, then twisted off to the north. I became aware that we were coursing beside another highway, draped along a ledge a few stories above the water level. Occasionally, through the trees, I could see motorists. I waved. They didn’t see me.

But during the hundred times I’ve driven this same stretch of Highway 17, my eyes were always sweeping this creek. I would’ve seen me. I would’ve waved back.

It ended too soon, abruptly dumping us into the Gasconade River at a picturesque spot beneath a towering bluff. As we carried our kayaks up a steep bank, I turned to say a silent prayer for the mudpuppies who struggle to survive beneath these waters. And I said goodbye to the second-most overlooked stream in Missouri.

Next time you’re driving along old Route 66 through Waynesville, look down as you cross Roubidoux Creek. I’ll be waving.

See more at JohnDrakeRobinson.com/blog. His books, Coastal Missouri and A Road Trip Into America’s Hidden Heart are available at independent bookstores and online booksellers everywhere.

Rescued From The Devil

May 2015

by JOHN DRAKE ROBINSON

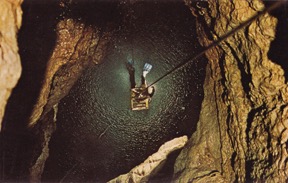

We left our canoes after a delightful Wednesday float down to Akers Ferry, which connects the wilderness north of the Current River to the wilderness on the south. The late afternoon sun gave us time to check out the world’s most dramatic sinkhole named after Satan.

We left our canoes after a delightful Wednesday float down to Akers Ferry, which connects the wilderness north of the Current River to the wilderness on the south. The late afternoon sun gave us time to check out the world’s most dramatic sinkhole named after Satan.

Read More...

Read More...

The Good Bad-Ass Samaritan

February 2015

by JOHN DRAKE ROBINSON

Home was calling. It was Friday, and the sun’s heat was shimmering on the highway ahead of me. Erifnus, my car, pointed her nose toward Columbia. By then, she’d show 290,000 miles on her odometer.

Home was calling. It was Friday, and the sun’s heat was shimmering on the highway ahead of me. Erifnus, my car, pointed her nose toward Columbia. By then, she’d show 290,000 miles on her odometer.

Read More...

Read More...